IIFT 2008 Question Paper

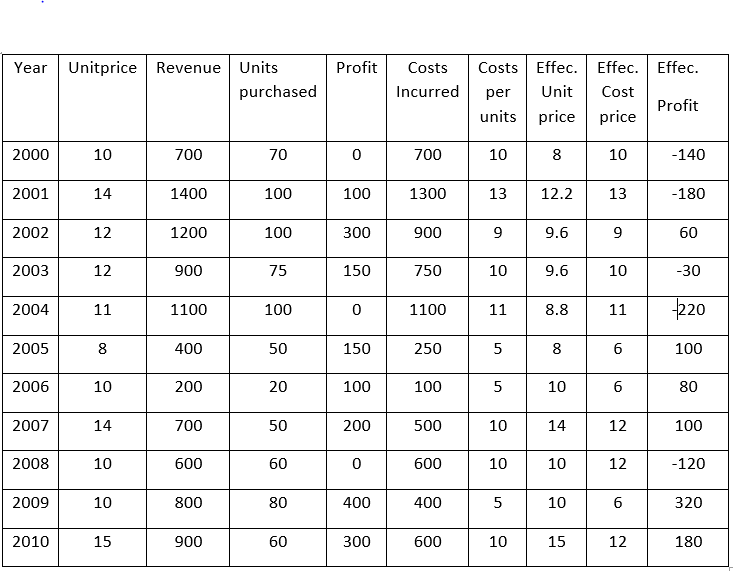

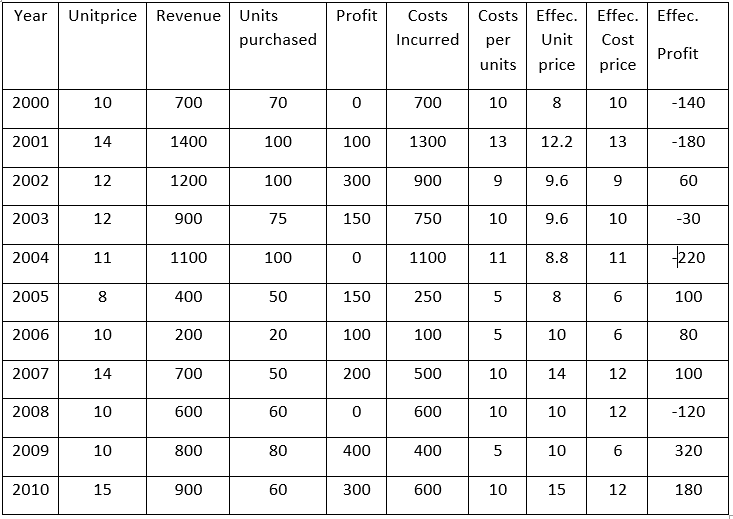

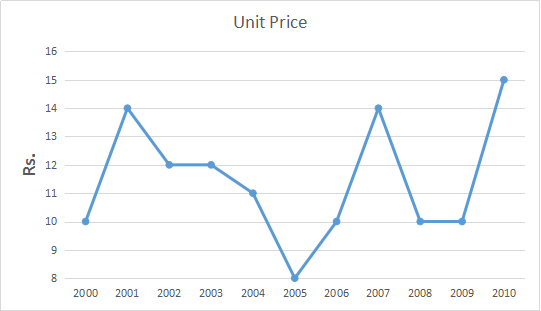

Answer the questions based on the following two graphs, assuming that there is no fixed cost component and all the units produced are sold in the same year.

Year wise graph of price of a unit

Year wise graph of revenue and total profit.

IIFT 2008 - Question 81

In which year per unit cost is HIGHEST?

IIFT 2008 - Question 82

What is the approximate average quantity sold during the period 2000-2010?

IIFT 2008 - Question 83

If volatility of a variable during 2000-2010 is defined as $$\frac{Maximum Value - Minimum Value}{Average Value}$$, then which of the following is TRUE ?

IIFT 2008 - Question 84

If the price per unit decreases by 20% during 2000-2004 and cost per unit increases by 20% during 2005-2010, then during how many number of years there is loss?

IIFT 2008 - Question 85

If the price per unit decreases by 20% during 2000-2004 and cost per unit increases by 20% during 2005-2010, then the cumulative profit for the entire period 2000-2010 decreases by:

Read the passage carefully and answer the questions given at the end of each passage:

Turning the business involved more than segmenting and pulling out of retail. It also meant maximizing every strength we had in order to boost our profit margins. In re-examining the direct model, we realized that inventory management was not just core strength; it could be an incredible opportunity for us, and one that had not yet been discovered by any of our competitors.

In Version 1.0 the direct model, we eliminated the reseller, thereby eliminating the mark-up and the cost of maintaining a store. In Version 1.1, we went one step further to reduce inventory inefficiencies. Traditionally, a long chain of partners was involved in getting a product to the customer. Let’s say you have a factory building a PC we’ll call model #4000. The system is then sent to the distributor, which sends it to the warehouse, which sends it to the dealer, who eventually pushes it on to the consumer by advertising, “I’ve got model #4000. Come and buy it.” If the consumer says, “But I want model #8000,” the dealer replies, “Sorry, I only have model #4000.” Meanwhile, the factory keeps building model #4000s and pushing the inventory into the channel.

The result is a glut of model #4000s that nobody wants. Inevitably, someone ends up with too much inventory, and you see big price corrections. The retailer can’t sell it at the suggested retail price, so the manufacturer loses money on price protection (a practice common in our industry of compensating dealers for reductions in suggested selling price). Companies with long, multi-step distribution systems will often fill their distribution channels with products in an attempt to clear out older targets. This dangerous and inefficient practice is called “channel stuffing”. Worst of all, the customer ends up paying for it by purchasing systems that are already out of date

Because we were building directly to fill our customers’ orders, we didn’t have finished goods inventory devaluing on a daily basis. Because we aligned our suppliers to deliver components as we used them, we were able to minimize raw material inventory. Reductions in component costs could be passed on to our customers quickly, which made them happier and improved our competitive advantage. It also allowed us to deliver the latest technology to our customers faster than our competitors.

The direct model turns conventional manufacturing inside out. Conventional manufacturing, because your plant can’t keep going. But if you don’t know what you need to build because of dramatic changes in demand, you run the risk of ending up with terrific amounts of excess and obsolete inventory. That is not the goal. The concept behind the direct model has nothing to do with stockpiling and everything to do with information. The quality of your information is inversely proportional to the amount of assets required, in this case excess inventory. With less information about customer needs, you need massive amounts of inventory. So, if you have great information – that is, you know exactly what people want and how much - you need that much less inventory. Less inventory, of course, corresponds to less inventory depreciation. In the computer industry, component prices are always falling as suppliers introduce faster chips, bigger disk drives and modems with ever-greater bandwidth. Let’s say that Dell has six days of inventory. Compare that to an indirect competitor who has twenty-five days of inventory with another thirty in their distribution channel. That’s a difference of forty-nine days, and in forty-nine days, the cost of materials will decline about 6 percent.

Then there’s the threat of getting stuck with obsolete inventory if you’re caught in a transition to a next- generation product, as we were with those memory chip in 1989. As the product approaches the end of its life, the manufacturer has to worry about whether it has too much in the channel and whether a competitor will dump products, destroying profit margins for everyone. This is a perpetual problem in the computer industry, but with the direct model, we have virtually eliminated it. We know when our customers are ready to move on technologically, and we can get out of the market before its most precarious time. We don’t have to subsidize our losses by charging higher prices for other products.

And ultimately, our customer wins. Optimal inventory management really starts with the design process. You want to design the product so that the entire product supply chain, as well as the manufacturing process, is oriented not just for speed but for what we call velocity. Speed means being fast in the first place. Velocity means squeezing time out of every step in the process.

Inventory velocity has become a passion for us. To achieve maximum velocity, you have to design your products in a way that covers the largest part of the market with the fewest number of parts. For example, you don’t need nine different disk drives when you can serve 98 percent of the market with only four. We also learned to take into account the variability of the lost cost and high cost components. Systems were reconfigured to allow for a greater variety of low-cost parts and a limited variety of expensive parts. The goal was to decrease the number of components to manage, which increased the velocity, which decreased the risk of inventory depreciation, which increased the overall health of our business system.

We were also able to reduce inventory well below the levels anyone thought possible by constantly challenging and surprising ourselves with the result. We had our internal skeptics when we first started pushing for ever-lower levels of inventory. I remember the head of our procurement group telling me that this was like “flying low to the ground 300 knots.” He was worried that we wouldn’t see the trees.

In 1993, we had $2.9 billion in sales and $220 million in inventory. Four years later, we posted $12.3 billion in sales and had inventory of $33 million. We’re now down to six days of inventory and we’re starting to measure it in hours instead of days. Once you reduce your inventory while maintaining your growth rate, a significant amount of risk comes from the transition from one generation of product to the next. Without traditional stockpiles of inventory, it is critical to precisely time the discontinuance of the older product line with the ramp-up in customer demand for the newer one. Since we were introducing new products all the time, it became imperative to avoid the huge drag effect from mistakes made during transitions. E&O; – short for “excess and obsolete” - became taboo at Dell. We would debate about whether our E&O; was 30 or 50 cent per PC. Since anything less than $20 per PC is not bad, when you’re down in the cents range, you’re approaching stellar performance.

IIFT 2008 - Question 86

Find out the TRUE statement:

IIFT 2008 - Question 87

Find out the FALSE statement:

IIFT 2008 - Question 88

Choose the option which best matches the following sets:

IIFT 2008 - Question 89

Find out the FALSE Statement:

Read the passage carefully and answer the questions given at the end of each passage:

My comrade and I had been quartered in Jamaica, and from there we had been drafting off to the British settlement of Belize, lying away west and north of the Mosquito Coast. At Belize there had been great alarm of one cruel gang of pirates (there were always more pirates than enough in those Caribbean Seas), and as they got the better of our English cruisers by running into out-of-the-way creeks and shallows, and taking the land when they were hotly pressed, the governor of Belize had received orders from home to keep a sharp look-out for them along shore. Now, there was an armed sloop came once a year from Port Royal, Jamaica, to the Island, laden with all manner of necessaries to eat, and to drink, and to wear, and to use in various ways; and it was aboard of that sloop which had touched at Belize, that I was standing, leaning over the bulwarks.

The Island was occupied by a very small English colony. It had been given the name of Silver-Store. The reason of its being so called, was, that the English colony owned and worked a silver-mine over on the mainland, in Honduras, and used this Island as a safe and convenient place to store their silver in, until it was annually fetched away by the sloop. It was brought down from the mine to the coast on the backs of mules, attended by friendly local people and guarded by white men; from thence it was conveyed over to Silver-Store, when the weather was fair, in the canoes of that country; from Silver-Store, it was carried to Jamaica by the armed sloop once a-year, as I have already mentioned; from Jamaica, it went, of course, all over the world.

How I came to be aboard the armed sloop is easily told. Four-and-twenty marines under command of a lieutenant - that officer’s name was Linderwood - had been told off at Belize, to proceed to Silver-Store, in aid of boats and seamen stationed there for the chase of the Pirates. The Island was considered a good post of observation against the pirates, both by land and sea; neither the pirate ship nor yet her boats had been seen by any of us, but they had been so much heard of, that the reinforcement was sent. Of that party, I was one. It included a corporal and a sergeant. Charker was corporal, and the sergeant’s name was Drooce. He was the most tyrannical non- commissioned officer in His Majesty’s service.

The night came on, soon after I had had the foregoing words with Charker. All the wonderful bright colours went out of the sea and sky in a few minutes, and all the stars in the Heavens seemed to shine out together, and to look down at themselves in the sea, over one another’s shoulders, millions deep.

Next morning, we cast anchor off the Island. There was a snug harbour within a little reef; there was a sandy beach; there were cocoa-nut trees with high straight stems, quite bare, and foliage at the top like plumes of magnificent green feathers; there were all the objects that are usually seen in those parts, and I am not going to describe them, having something else to tell about.

Great rejoicings, to be sure, were made on our arrival. All the flags in the place were hoisted, all the guns in the place were fired, and all the people in the place came down to look at us. One of the local people had come off outside the reef, to pilot us in, and remained on board after we had let go our anchor.

My officer, Lieutenant Linderwood, was as ill as the captain of the sloop, and was carried ashore, too. They were both young men of about my age, who had been delicate in the West India climate. I thought I was much fitter for the work than they were, and that if all of us had our deserts, I should be both of them rolled into one. (It may be imagined what sort of an officer of marines I should have made, without the power of reading a written order. And as to any knowledge how to command the sloop—Lord! I should have sunk her in a quarter of an hour!) However, such were my reflections; and when we men were ashore and dismissed, I strolled about the place along with Charker, making my observations in a similar spirit.

It was a pretty place: in all its arrangements partly South American and partly English, and very agreeable to look at on that account, being like a bit of home that had got chipped off and had floated away to that spot, accommodating itself to circumstances as it drifted along. The huts of the local people, to the number of five- and-twenty, perhaps, were down by the beach to the left of the anchorage. On the right was a sort of barrack, with a South American Flag and the Union Jack, flying from the same staff, where the little English colony could all come together, if they saw occasion. It was a walled square of building, with a sort of pleasure-ground inside, and inside that again a sunken block like a powder magazine, with a little square trench round it, and steps down to the door.

Charker and I were looking in at the gate, which was not guarded; and I had said to Charker, in reference to the bit like a powder magazine, “That’s where they keep the silver you see;” and Charker had said to me, after thinking it over, “And silver ain’t gold. Is it, Gill?”

IIFT 2008 - Question 90

Find out the TRUE statement: